It’s my mother’s 7th birthday. She goes off to school happily to share the excitement of the day. But jealousy rears its ugly head and a little boy says, “In any case, you’re adopted”. When she gets home from school, she learns the heartbreaking truth – well, part of it, anyway.

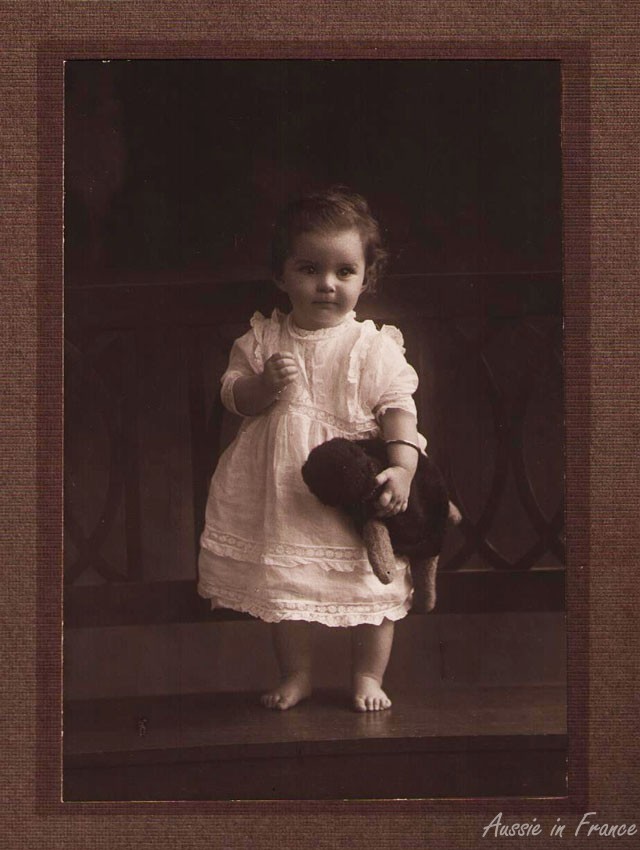

Her real mother, Ada, conceived her in the ship that took her family – her husband and four children aged 2 to 10 – to Australia. She died in childbirth in Brisbane in 1920. My mother, Ada Joan, who only weighed one kilo at birth was unofficially adopted by an older couple who didn’t have any children of their own. To keep her alive, her foster mother strapped her to her chest at night.

When my mother was eight months old, her father took the other children back to England, promising to send for her when she was old enough to travel. He never did and never made any contact with her at any time.

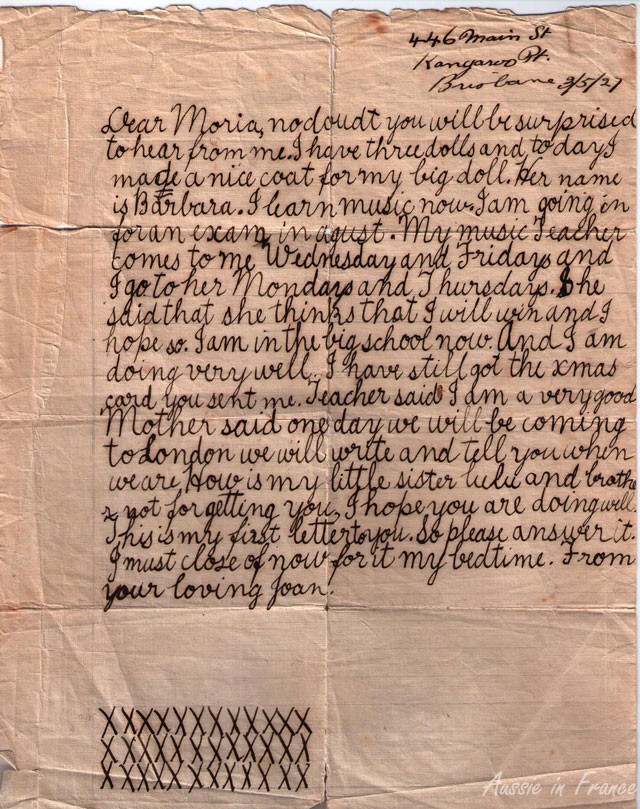

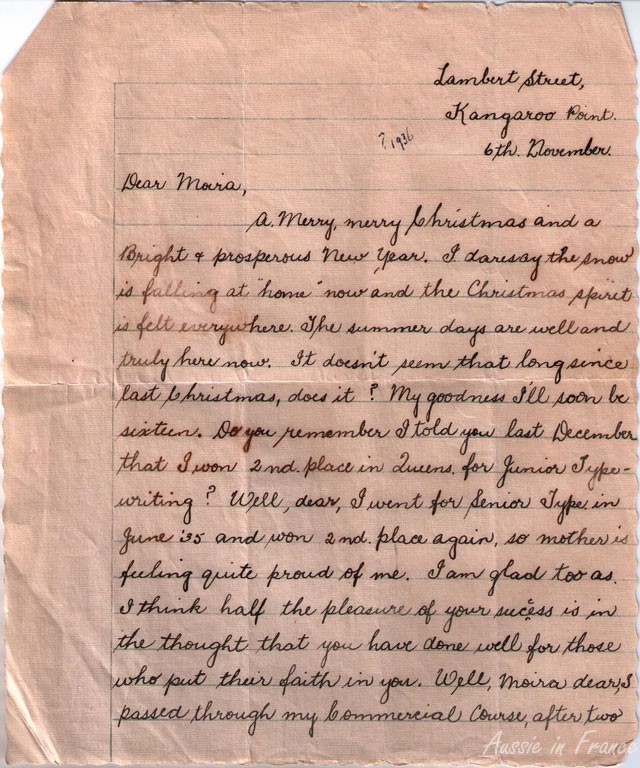

It’s now a few months after her 7th birthday and my mother has started corresponding with her older sister, Moira, and will do so until she’s fifteen. The letters are poignant.

But Moira wants to visit her in Australia so my mother cuts off all correspondence because, as she explains to me later, she is afraid her sister won’t like her.

The year she turns 18, my mother’s foster parents, whom she loves very much, both die within six months of each other leaving her no family at all. By then she is living and working in the Crown Sollicitor’s office in Canberra. She gets engaged to a man called Jack, I think, but like so many other young men at the time, her fiancé is killed in World War II.

Back in Brisbane after the war, she meets my father, the oldest of a family of 9 children from a sheep property in northern New South Wales. They get married in Brisbane in 1948. After three years without any sign of pregnancy, they are about to adopt a baby when my sister is conceived.

I am born the next year and my two brothers soon come along, each spaced three years apart. My mother has two miscarriages after that. She is devastated. She wants a big family. We are on holidays on the Atherton Tablelands when she miscarries the second time. I don’t understand what’s happening but suddenly my mother is in hospital.

In 1966, my sister is 14. We’re holidaying on a nearby coral island and are visiting friends. My brothers are playing out the back of the house and my sister goes to check on them. The next thing, one of the boys comes back to tell us that a rock has fallen on my sister. Death must have been instant. There is absolutely no explanation why a ten-ton rock should have moved as that precise moment.

My mother has lost the first person of her own flesh and blood she has ever known. When I have my own son and daughter, I realise what it must have been like. I am utterly paranoid the year each of them turns 14. I am always aware of the great fragility of the life of a child.

Many years later, I am visiting my mother who is on holiday in London. She asks me to go with her to the births and deaths registry at Somerset House. We track down her parents’ birth and marriage certificates and are able to find some addresses in the north of England. None of them, however, produce any results.

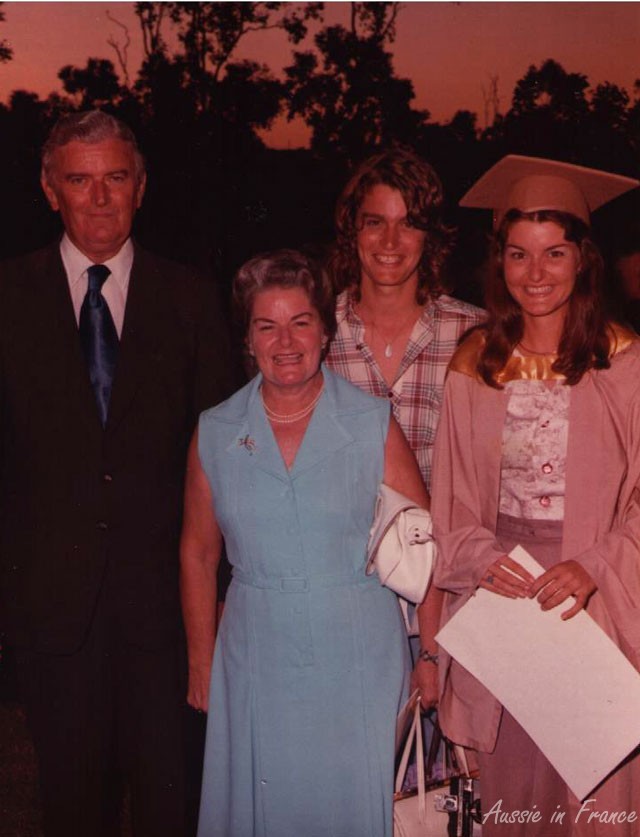

It is not until my mother is 70 that a genealogy expert at the university in Townsville tracks down her older sister Moira who is then a retired registered nurse living in Canada. My parents go to meet her in Toronto and learn the rest of the story which proves even more devastating.

It turns out that my mother’s parents were travelling out to Australia to see her mother’s mother who, for some reason no one seems to know, was living in Brisbane at the time. My mother’s maternal grandmother LIVED IN THE SAME STREET as my mother until she died, without ever acknowledging her in any way. She is buried in the Kangaroo Point cemetary in Brisbane.

Moira has kept my mother’s letters all these years and that is how we have them today. She is able to give very little news of the rest of the family. One of her brothers also emigrated to Canada and was blown up in a laboratory accident. She herself has never married. The two sisters keep in regular contact after that, mainly at my mother’s instigation, but after my father dies in 1993, there are no more trips overseas so the two sisters don’t ever meet again.

After my mother’s death in the year 2000, I try to phone Moira but get no answer so I send a card. There is no response. A couple of years later my younger brother receives a letter from a sollicitor in Canada telling us that Moira has left her very small estate to a charity and asking if we want to contest the will, which we don’t of course.

In today’s world of the Internet and social media, my mother’s story would have ended differently, I believe. Australia back in 1920 was really at the end of the earth. Communication was slow and difficult. But it doesn’t explain her grandmother’s attitude, does it?