In this week’s Blogger Round-Up, Gigi from French Windows explains her love/hate relationship with French articles, while Maggie LaCoste from Experience France by Bike gives us a detailed explanation of French rail’s new site for cyclists in English. To finish off, Anda from Travel Notes and Beyond takes us to a most unusual place in Dresden that has singing pipes. Enjoy!

Feminine Articles

By Gigi from French Windows, failed wife and poet, terrible teacher and unworthy mother of three beautiful girls, who has lived in France for over twenty years and gives glimpses of her life with a bit of culture thrown in.

It’s International Women’s Day so I thought I’d write a piece about my struggle, here in France, with all things feminine.

It’s International Women’s Day so I thought I’d write a piece about my struggle, here in France, with all things feminine.

Well, not all things feminine. Nouns mostly. After twenty-seven years in this country, you’d think I’d have got the hang of this le/la, un/une business but pas du tout. I provide endless amusement for my French friends and colleagues because I still get it wrong.

I mean, some words just sound feminine to my worryingly gender-stereotyped (I’ve just realized) mind. Like nuage…soft and fluffy, it’s actually masculine. Or pétale, which is also masculine. And then there is victimeand personne, which are feminine. So when the newsreader refers to a male murder victim as ‘elle’, I get terribly confused. Read more

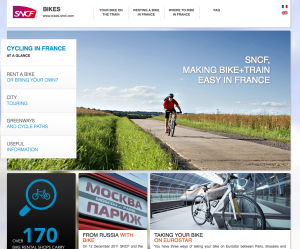

New French Rail Website for Bicyclists

by Maggie LaCoste from Experience France by Bike, an American who loves biking anywhere in Europe, but especially France, which has the perfect combination of safe bike routes, great food, great weather and history.

SNCF, operator of France’s national rail service has a new website designed to help bicyclists navigate the train network. The website is easy to navigate, is full of information you should know if you plan to carry a bike on a train while bicycling in France and it’s in English. The website doesn’t make it any easier to take your bike on a train, it does help you understand the rules. Since there has never been a centralized source of information for travel on French trains with bikes, this website is a huge step forward.Whether you need information on bringing a bike into France on a train, traveling via train with a bike while in France, where to rent a bike near a train station or where to ride, this website will provide you with the basic information you need. Here’s a basic rundown of information on the website, and quick links if you need more information. Read more

SNCF, operator of France’s national rail service has a new website designed to help bicyclists navigate the train network. The website is easy to navigate, is full of information you should know if you plan to carry a bike on a train while bicycling in France and it’s in English. The website doesn’t make it any easier to take your bike on a train, it does help you understand the rules. Since there has never been a centralized source of information for travel on French trains with bikes, this website is a huge step forward.Whether you need information on bringing a bike into France on a train, traveling via train with a bike while in France, where to rent a bike near a train station or where to ride, this website will provide you with the basic information you need. Here’s a basic rundown of information on the website, and quick links if you need more information. Read more

The Singing Drain Pipes of Kunsthofpassage

by Anda from Travel Notes & Beyond, the Opinionated Travelogue of a Photo Maniac, is a Romanian-born citizen of Southern California who has never missed the opportunity to travel.

I didn’t know anything about this site before our trip to Germany. One day, as I was searching the net for places of interest in Dresden, I stumbled upon a picture of a strange, funny building with a big giraffe on it. It was the Kunsthofpassage. I tried to find out more about this curious spot, but the information at hand was scarce and very conflicting: some called it a “masterpiece”, others “a waste of time”. But the picture of that building was very intriguing so I wanted to visit it. Read more

I didn’t know anything about this site before our trip to Germany. One day, as I was searching the net for places of interest in Dresden, I stumbled upon a picture of a strange, funny building with a big giraffe on it. It was the Kunsthofpassage. I tried to find out more about this curious spot, but the information at hand was scarce and very conflicting: some called it a “masterpiece”, others “a waste of time”. But the picture of that building was very intriguing so I wanted to visit it. Read more